You may have heard the term 'Plastic Māori' thrown around, perhaps between two cousins gossiping about that one cousin who lives in Aussie and always looks awkward when they come back to their marae to visit. Or directed at you by a baffled and embarrassed whaea (aunty) who can't believe you don't eat kaimoana (seafood). Or a comment under the breath about how pale you are, so how could you possibly be a 'real' Māori? Or perhaps the term has even come out of your own mouth, directed at another person, behind their back, or even referring to yourself to instantly lower the expectations others should have of you when you step into a Māori context. Whether or not you have given the term much thought (let alone heard of it), this article dives a bit deeper into the term, what it means, its effects on our Māori community, and why the term should stop being used altogether.

What does 'Plastic Māori' mean?

Over generations, the term 'Plastic Māori' has evolved to describe the disconnect some Māori have from their cultural knowledge, whakapapa, language and tikanga, often resulting from not being raised in the culture. This disconnection, frequently a consequence of colonisation and language suppression, highlights the complex challenges many face in reclaiming their Māori identity. The term 'Plastic Māori' implies that someone is not 'authentically' Māori and may be seen as an imposter or lacking in some way. However, Māori identity and culture are complex and multifaceted and can vary depending on a person's upbringing, iwi (tribe), geographical location, generational history, access to education, financial situation, and personal experience.

Why is the term 'Plastic Māori' harmful?

Using derogatory terms like 'Plastic Māori' to judge or exclude individuals from the Māori community based on arbitrary or elitist standards is not helpful or constructive. In fact, it can be incredibly damaging and hurtful to those who are targeted by such language.

It's crucial to recognise that there are many factors that can influence a person's ability to access and engage with their Māori culture. These include historical factors such as colonisation, the forced assimilation of Māori children into European-style schools where speaking Māori was forbidden, and the intergenerational trauma that resulted from these experiences.

Furthermore, not everyone has equal access to learning about their Māori culture, whether due to geographic location, financial barriers, or other factors. It's important to recognise that this does not make someone any less Māori.

The use of the term 'Plastic Māori' can also have the unintended consequence of discouraging some Māori from exploring and reclaiming their cultural identity. The fear of not being 'Māori enough' or of being judged by others as 'fake' or 'inauthentic' can be a significant barrier for some Māori in engaging with their culture.

Why should we stop using the term 'Plastic Māori'?

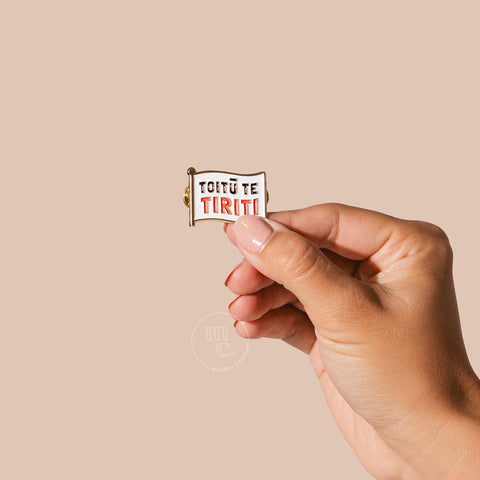

It's crucial to recognise that whakapapa (genealogy) is the only qualification for being Māori. A person's connection to their Māori ancestry and (whakapapa) is the only relevant factor in determining their Māori identity. Judging someone's Māori identity or cultural knowledge based on arbitrary or elitist standards is unfair and unproductive, and nothing productive will come of belittling and criticising fellow Māori who are on their reclamation journey.

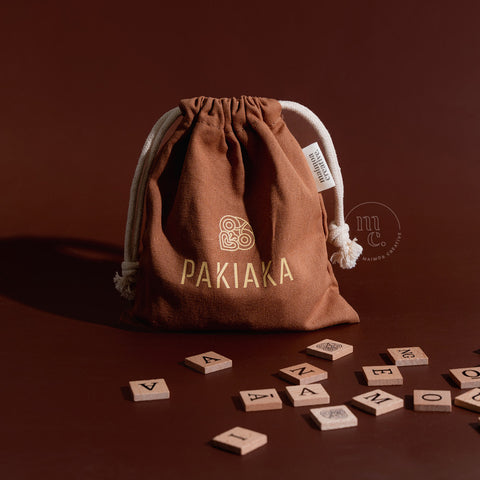

Another aspect that is important to understand when it comes to the kaupapa of deeming someone's Māoritanga, is that learning te reo (the Māori language), tikanga (cultural practices), karakia (prayers), waiata (songs), whakapapa (genealogy) and other aspects of Māori culture helps individuals connect with their Māoritanga (Māori identity and heritage), but it does not determine their level of 'Māori-ness.'

There is no one-size-fits-all definition of what it means to be Māori or to practice Māori culture.

What term should be used instead?

Māori. Just Māori. Instead of using derogatory terms like 'Plastic Māori,' we should strive to create a welcoming and inclusive environment within the Māori community. This means recognising that individuals may have varying levels of exposure to and knowledge of their culture, and working together to promote understanding and cultural exchange.

In conclusion, it's important to recognise the damaging effects of using derogatory terms like 'Plastic Māori' to judge or exclude members of the Māori community. Learning about Māori culture and language should be celebrated and encouraged, but it should never be used as a measure of someone's authenticity as a Māori individual. Ultimately, whakapapa (genealogy) is the only qualification for being Māori, and it is crucial that we recognise and celebrate the diversity within our people to create a stronger and more inclusive community that honours, values, and provides a safe space for all its members.

References: